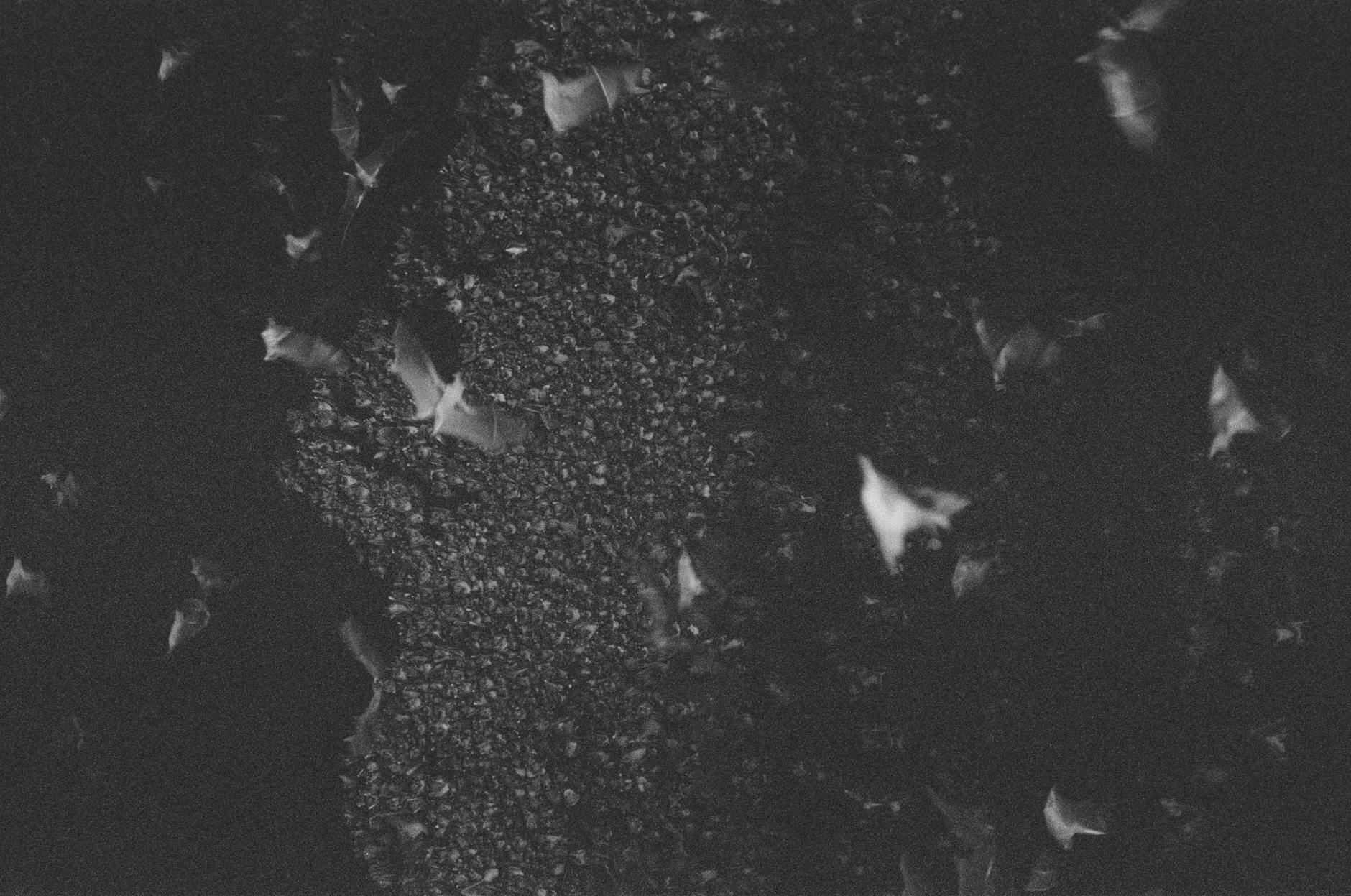

This Halloween, we are checking in with our “bat-ty” friends. North American populations of bats have been severely decreased by a deadly fungus, known as Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which results in a disease called ‘white-nose syndrome’. There are currently 13 species of hibernating bats known to have been impacted by the disease (Center for Biological Diversity). Having toured a cave recently, our guide ensured that everyone decontaminated their shoes before entering the cave as spores can travel on clothing, gear and shoes. Since 2006, estimations suggest that the fungus has killed approximately 6.7 million bats and has even wiped out entire hibernating colonies. Bats are very important for pest control as they consume millions of pounds of insects every year. That means, with less bats around, insect populations have multiplied resulting in heavy use of pesticides by some farmers. If farmers were to compensate bats for their services, they would have to pay $3.7-53 billion dollars annually (Center for Biological Diversity). That could pay for quite a few bat mobiles…

In 2017, we talked about how bats infected with white-nose syndrome have a higher metabolism and lose more body water than those who are not infected. This causes infected animals to use stored body fat as they arouse more often during hibernation in search of water and a cooler place to sleep. By choosing a cooler spot (literally), the animals have a better chance of entering a deeper state of hibernation and slowing fungal growth (Turner et al., 2021).

Researchers at the University of Illinois found a chemical that could coat the spores and prevent them from growing. Armed with this knowledge, a team of researchers tested the chemical, polyethlyene glycol 8000 (PEG), by spraying the walls of a hibernaculum during the summers of 2018 and 2019 and waited. When they returned to test the bats, they were pleased to discover that their preventive measures decreased the number of white-nose syndrome cases. Importantly, the researchers did not find any evidence of the treatment itself harming the bat colony (Sewall et al., 2023). The team is currently conducting larger studies to see whether PEG can prevent the spread of white-nose syndrome in other populations and locations. The team has also tested cooling systems and found that simply lowering the temperature to 3-6 degrees C improved the bat’s survival odds (Turner et al., 2021). Their next big project involves creating an artificial hibernaculum complete with tubes and a pool of water to hopefully attract winter bat guests and improve their survival and health. Another team of researchers is focused on installing native plants along flight corridors to attract insects and ensure that bats have easy access to foods when they emerge from hibernation so they do not have to work so hard to forage (NYT).

In Michigan, a team of researchers discovered a population of little brown bats, Myotis lucifugus, that appears to have developed resistance to the fungus even though it has been detected in their hibernaculum, located in the Tippy Dam spillway. This particular hibernaculum is different from many others as light is able to penetrate the area through small holes. The researchers suspect that exposure to natural light maintains the bat’s circadian rhythm such that many of the bats experience arousals at the same time and can thermoregulate as a group. For this reason, they suspect adding light to regulate the animal’s circadian rhythm may be an additional strategy to mitigate mass die-offs from white-nose syndrome (Gmutza et al., 2024).

European populations of bats, where the fungus originated, have developed immune resistance to the disease. In recent years, genetic tests have revealed some modifications in North American bats that have survived white-nose syndrome outbreaks as well. In addition to behavioral responses to infections, such as moving to colder parts of a cave, the bats are also increasing their fat stores prior to hibernation (Cheng et al., 2024).

Sources:

Center for Biological Diversity

Bat Conservation International

BJ Sewall, GG Turner, MR Scafini, MF Gagnon, JS Johnson, MK Keel, E Anis, TM Lilley, JP White, CL Hauer, BE Overton. Environmental control reduces white-nose syndrome infection in hibernating bats. Animal Conservation. 26(5): 642-653, 2023.

GG Turner, BJ Sewall, MR Scafini, TM Lilley, D Blitz, JS Johnson. Cooling of bat hibernacula to mitigate white-nose syndrome. Conservation Biology. 36(2): e13803, 2021.

HJ Gmudza, RW Foster, JM Gmutza, GG Carter, A Kurta. Survival of hibernating little brown bats that are unaffected by white-nose syndrome: Using thermal cameras to understand arousal behavior. PLoS One. 19(2): e0297871, 2024.

TL Cheng, AB Bennett, MT O’Mara, GG Auteri, WF Frick. Persist or Perish: Can bats threatened with extinction persist and recover from white-nose syndrome? Integrative and Comparative Biology. 64(3): 807-815, 2024.

Categories: Comparative Physiology, Illnesses and Injuries, Nature's Solutions, Stress

Tags: animals, Bats, biology, nature, science, white-nose syndrome, wildlife