Cell membranes are incredibly complex environments that play crucial roles in interacting with other cells, sensing specific molecules in the body, controlling what crosses the membrane, and other vital functions. The composition of these membranes varies between organs in an animal, between similar organs in different species, and even between individuals of the same species. Think of cell membranes as gatekeepers, responsible for detecting various chemical signals (such as ions or molecules), mechanical forces (like stretch or pressure), and electromagnetic waves. These signals enable cells to communicate with each other, both within and between organs, helping organisms respond to changes in their environment. However, disruptions in these vital functions can contribute to disease and impair an organism’s ability to adapt to environmental stressors.

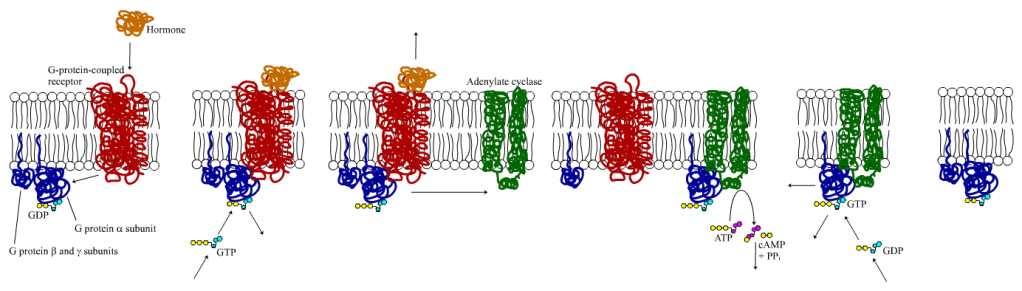

There are many different types of receptors within the cell membrane, each specializing in detecting specific signals. One such receptor type are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), which first appeared over 1 billion years ago, and was the focus of a recent review published in Physiological Reviews. Found in fungi, plants and animals, GPCRs helps organisms interact with their environment and respond to various internal signals. In fact, GPCRs are involved in detecting visual, sound, taste, smell, and touch sensations. They are so diverse in their ability to sense different signals that humans have about 800 GPCRs genes, with roughly half dedicated to sensory perceptions of taste, light, and smell. In contrast, African elephants have over 2000 GPCR genes dedicated to the sense of smell alone, while birds have only around 141 odor-detecting GPCRs. Changes in GPCRs are observed in animals adapted to nocturnal schedules, aquatic environments, and even flight. Changes may also influence the types of foods animals prefer to eat…I wonder whether kids have different GPCRs than adults?

Let’s take a closer look at how changes in GPCRs have enabled animals to adapt to various stressors and environments.

Living in the dark

Some species adapted to environments with dim light or nocturnal lifestyles are missing certain opsin receptors that detect colors. As a result, they may not see as many colors as other species. For example, while many species of birds can see four colors (tetrachromacy), penguins and owls can only see three (trichromacy). Bats, seals, dolphins, whales, sharks, and some fish living in dark environments can only see one color (monochromacy), while others, such as lanternfish, live so deep in the ocean that they can’t perceive color at all.

Choosing what to eat

Similar to smell, an animal’s sense of taste helps it identify foods to eat avoid. Humans can sense six tastes: ammonium, salt, sour, sweet, bitter, and umami, and GPCRs are responsible, at least in part, for detecting sweet, bitter, and umami flavors. Salts and vitamins are crucial for maintaining an organism’s homeostasis, so it’s no surprise that animals have evolved a taste for salty and sour foods. Detecting bitter tastes or ammonium also helps animals avoid foods that may be toxic or spoiled. In fact, the presence of bitter receptors seems to coincide with the increasing presence of plants in the environment about 430 million years ago. Our taste for sweet and umami foods also ensures that we consume plenty of carbohydrates and proteins in our diets. On the other hand, ocean dwelling species have a reduced ability to discriminate tastes as the high salt environment in which they live masks most flavors, making these tastes receptors unnecessary. Similarly, too much salt in our food can easily ruin the taste of a meal.

It is not surprising that many carnivorous species, such as seals, dolphins, spotted hyenas and Asian otters have lost their “sweet tooth,” while others, like ferrets and Canadian otters have kept it. In contrast, some plant-eating animals, such as pandas, have lost certain umami associated GPCRs. Other variations in GPCRs are thought to have contributed to the domestication of feed animals and even dogs.

Other cool functions of GPCRs

Specialized GPCRs also help bats and dolphins echolocate. Some GPCR genes are associated with pigmentation and coat color, such as those regulating melanocyte stimulating hormones, which can control whether an animal is camouflaged in its environment. Other GPCRs have helped animals adapt to aquatic life, influencing the development of hair, coats, and bone mass. Moreover, others related to water balance and light coat colors are thought to have helped animals adapt to hot, dry desert environments, while some have contributed to adaptation to cold and hypoxic environments.

What about humans?

Studies show that human populations also have variations in GPCRs compared to our ancestors. For example, modern humans have better stereoscopic vision and the ability to detect colors, which likely evolved as we transitioned from forested habitats to open landscapes. Although our sense of smell is weaker than that of many other animals, we rely more on vision and social cues. We also have a greater taste for sweet foods, especially ripe fruits that are easy to eat and digest, compared to our ancestors. Additionally, exposure to numerous pathogens has shaped our immune system, resulting in variations in immune-related GPCRS.

Source:

T Schöneberg. Modulating vertebrate physiology by genomic fine-tuning of GPCR functions. Physiological Reviews. 2024. Doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2024

- Brain Power on a Budget: How Bullfrogs Survive Without Oxygen

- Surviving the heat: How humans and animals adapt to hot environments

Categories: Comparative Physiology, Diet and Exercise, Environment, Extreme Animals, Hibernation and Hypoxia, Nature's Solutions, Ocean Life

Tags: American Physiological Society, biology, cell, food, GPCR, health, medicine, nutrition, Physiological Reviews, science